What Makes Fortified International Borders So Intriguing

Shôn Ellerton, Dec 3, 2017

Have you ever wondered why people used to flock to the Iron Curtain just to be able to see the other side? Why is there a such a sense of thrill when crossing a fortified international border?

Let’s take a hypothetical situation. If you were ever invited to be a caretaker of your friend’s ancient mansion over a month or so while he or she went on a long vacation and then were told that you should never enter a certain room, you know full well what you will be doing as soon as your friend leaves you to your own devices. That’s right. Your curiosity would grow and grow until it got just got so intolerable that you muster up the courage only to then cautiously enter the room having mixed feelings of trepidation, fear and wonder.

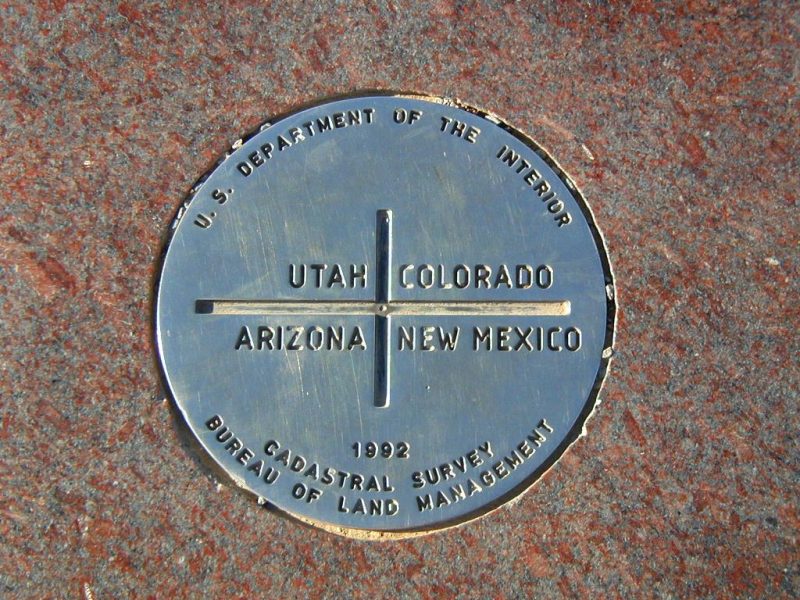

Some of us enjoy the experience of being able to walk, sit or lie across geographical boundaries whether it is sitting cross-legged on the point where four US states converge together or lying across the floor of the Haskell Free Library located in Quebec where the US-Canada boundary runs across the floor as marked by a black strip of tape.

But many of us are even more fascinated by what lurks behind a barrier, wall or some other form of obstruction we find difficult or simply unable to cross. This is especially true with fortified international borders, the most extreme example being the heavily militarised North-South Korean border. On my excursion to North Korea during 2003, I took an opportunity to sit in a chair (pictured below) straddling the military demarcation line separating North and South Korea inside one of the blue negotiation huts at the DMZ.

My First Experience with the Iron Curtain

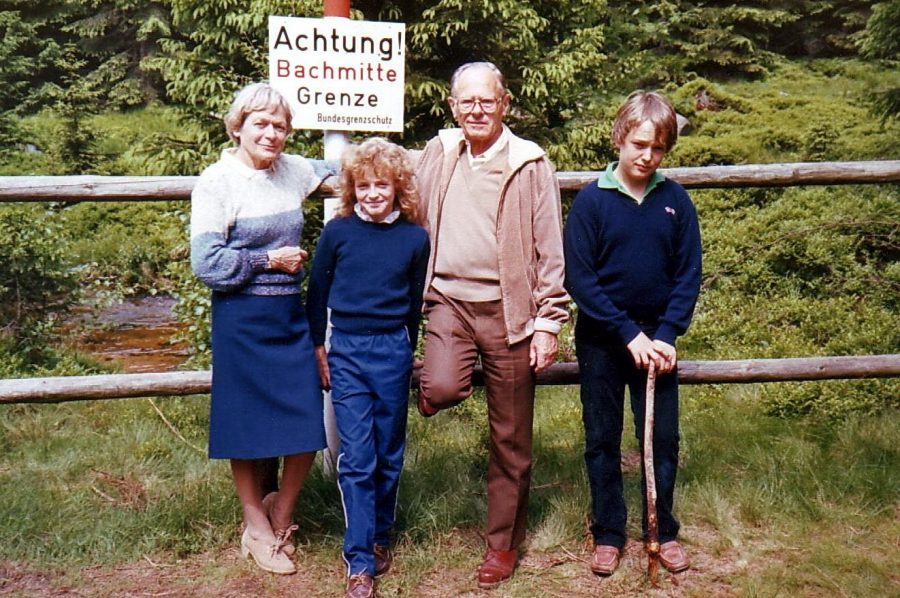

My fascination with fortified international borders may have all started in my youth back in 1984 whilst visiting my German grandparents who used to live not too far away from the Iron Curtain in the town of Wolfenbüttel, known for its production of Jägermeister, a famous alcoholic herbal liqueur. Not far away lies the picturesque Harz Mountains in which the Iron Curtain used to meander right through the middle of it. The Iron Curtain, since dismantled during 1991, separated West Germany and East Germany and comprised of a near-impenetrable barrier comprising of electric fences, vicious dogs, trigger-happy guards and minefields. We would drive through the Harz Mountains and, in quintessential German style, stop for coffee and cake and then go for a stroll along one of the many hiking paths leading to the bottom of the shallow valley separating us from Brocken, the Harz Mountain’s highest point. Walking down the valley and then up to Brocken would be impossible because, lying at the base of the valley was the Iron Curtain. One could not help but curiously gaze over the valley to the crest of Brocken and its scattering of building and antennas knowing all too well that, on the other side, was a totally different world, an unfree world where citizens are kept prisoners in their own country. It was a country where even listening to West German radio was a prisonable offence. We began to walk down from the café along one of the many trails leading towards the bottom of the shallow valley where the border lied. The air was clean and fragrant with the smell of conifer trees, the sky was blue with a scattering of clouds and the spring flowers were out bursting with colour amongst the freshly-growing forest grass. We suddenly approached a small creek flowing amongst the peaceful spruce trees on which stood on its nearest bank, a stark-looking warning sign displaying the following message: Achtung! Bachmitte Grenze, translated as Warning! Border through middle of creek. Pictured below is a very young picture of me along with my sister and late grandparents standing next to the warning sign.

Somewhere through the trees on the other side of the river was the Iron Curtain but we could not see it yet. We walked a little further and, there it was, visible through an opening in the trees. There was a strip of bare ground around fifty metres wide containing, no doubt, explosive mines bordered by a variety of concrete and electric barbed-wire fences. Watch towers could be seen at intervals down the strip and there on the other side was a peaceful-looking village. It looked like any other typical German village from where we were standing except behind its façade lay an alternative universe forbidden from prying Western eyes. Even citizens from the East were generally forbidden to come anywhere near 3km of the border. From that moment, I always held a fascination with international borders; especially those which are not meant to be crossed. Below is a photo I took looking across the Iron Curtain into East Germany in 1984.

The Grass is Greener on My Side of the Fence

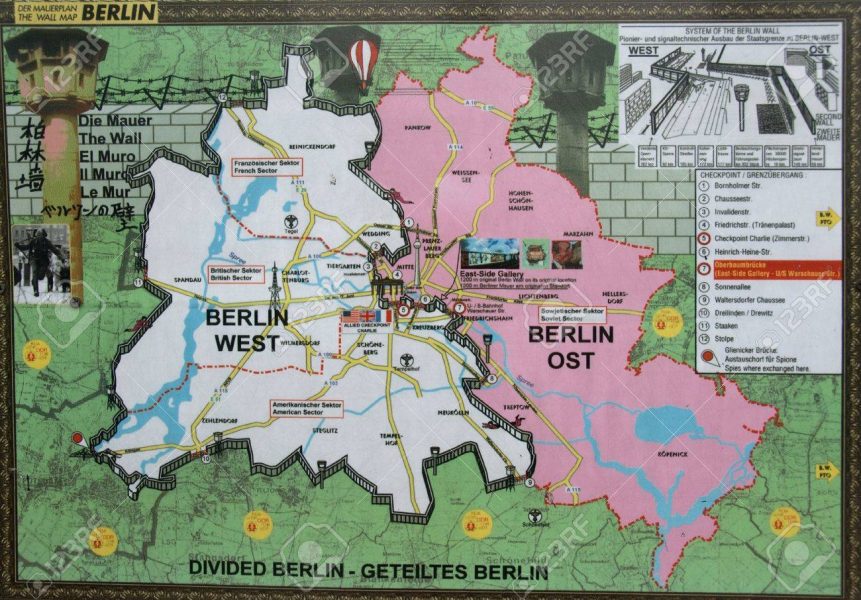

Growing up in Colorado during the 70s and early 80s, far away from any international boundaries, it blew my mind that, somewhere in the world, citizens could be kept prisoner in their own countries. I recall reading an article in a National Geographic magazine published during the late 70s of what life was like in, what was then known as, East Germany. The article, along with some fine photography, portrayed a controlled, bleak Orwellian world seemingly thrown back at least fifty years back into the past. Yet just on the other side of the Iron Curtain in the West, was the free and booming society which many of us are used to. The former Soviet Union, of course, was the most prominent example of such a controlled society where citizens were not able to leave freely; however, as far as borders are concerned, there was nothing separating more contrasting societies in such proximity to each other as the Iron Curtain dissecting East and West Germany, especially through the busy city of Berlin.

Now this is the interesting thing. We seem to be particularly intrigued when the other side is clearly not a better place to be almost to the point of relishing in the fact that we are far better to be here on this side rather than that side. A similar behaviour can be drawn from the countless movies and books based on dystopian futures clearly outselling those based on utopian societies. Conversely, many of us take an interest in knowing how the über-rich live, what it’s like to own your own private jumbo jet, or owning your own island; however, in most cases, all this tends to do is generate feelings of wanting, envy, lack of success, or even some degree of disgust. We then try to convince ourselves that the rich are just as unhappy as the poor but, in all honesty, most of us would like to have a little taste of their opulent lifestyle. When we read or watch material about unfortunates living a brutal or deprived lifestyle, we tend to thank our lucky stars that it is not happening to us. Human nature has an unhealthy predeliction of taking an interest in the dark and the morbid sometimes at the misfortunes of others, a term known as schadenfreude.

The Experience of Crossing a Fortified International Border

Those of you that have crossed a fortified international border into a country highly intolerant of individual freedoms or a country where you could ignorantly get into trouble by unexpectedly breaking a law that you were unaware of may have experienced a variety of mixed emotions ranging from fascination, excitement or even a sense of dread. The process of leaving the country can even be more daunting indeed. The story of Otto Warmbier who got arrested in January 2016 just as he was leaving North Korea allegedly for trying to steal propaganda posters and then being sent to a labour camp only to be sent back home in a coma in which, not long after, he died, most assuredly sent shivers down the spines for all of us who read about it.

Crossing a fortified border by foot, train or car is even more interesting. One’s curiosity is aroused as to what the border comprises of. You can’t help but wonder what it would be like to try to attempt to cross the border. Could you climb those walls? Would someone try to take a potshot at you? And what about those fences? Are they electrified? Would there be dogs and explosive mines? One of the most interesting transits through a ‘closed’ country, at least up until 1991, was travelling the 200 km stretch of autobahn from West Germany to West Berlin, a free island state surrounded by the reclusive and police-state of East Germany. This was known as the Helmstedt-Berlin Corridor. Travelling from Helmstedt to Berlin, you would first stop at Checkpoint Alpha at the West-East German border where you were given a briefing to ensure that you had enough fuel to make it across and ensure that you made the trip in less than 4-hour’s time. You would be given due warning not to pull over and take snappy photographs of the surrounding countryside or not to drive down the wrong exit ramp as this would, invariably, land you in a spot of bother. Once you have travelled the corridor and arrived at the border into West Berlin, East German officials along with their dogs (German shepherds of course!) would inspect your vehicles for potential stowaway defectors and only then will you be allowed to proceed into the free state of West Berlin through Checkpoint Bravo. I remember my own experience of driving through iconic Checkpoint Charlie, a crossing in the middle of Berlin between the East and the West. Although it was during the end of 1990 and, politically, the wall had already come down and East Germans were free to transit across, you still needed a visa to enter East Germany and there was a sense of thrill when the heavy metal barrier was lifted and you drove through no-man’s land complete with minefields (some being still active), electric fences (recently switched off) and razor-sharp barbed wire. During this time, the East German border guards were at ease and jovial often willing to have their photographs taken with you as this was a time of celebration when the two countries were about to be re-united. However, before this, it would have been a much more sombre affair. Below is a picture I took of no-man’s land whilst going through Checkpoint Charlie in 1990. Although the border had recently become inactive at the time, venturing into no-man’s land was still a dangerous place due to the possibility of the unfortunate possibility of running into a yet unremoved explosive mine.

The most daunting experience for me was back in 2003 when I was crossing the border by train into North Korea from China over the steel-girder bridge spanning across the River Yalu from the sprawling Chinese city of Dandong into the North Korean grey, decaying city of Sinujiu on my way to Pyongyang. This was when I attended an arranged tour by Koryo Tours (still operating today) in which entry to the Hermit Kingdom was via an overnight sleeper train from Beijing to Pyongyang. The train stopped for several hours at Dandong, the last Chinese city before crossing over the bridge of the River Yalu. At this point we disembarked and waited for the train to be re-assembled with, primarily, old East German livery before we were ushered back onboard the train. Before proceeding, our guide informed us that we will now be entering the DPRK (the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea) giving us a friendly warning not to take photographs out of the window. Of course, we all did! We were already prepared by the guide as to what we should not bring into the country. This included printed material including newspapers, mobile phones and of course, any religious material. It staggers me beyond belief the extent to what religious proselytisers will do to extend the word of God. Back in 2014, there was a 75-year-old Australian man based out of Hong Kong by the name of John Short who was arrested and detained in North Korea for distributing out Korean-translated Christian pamphlets around the various temples he visited. Taking his age into consideration, the authorities had him expelled from the country rather than being sent to a labour camp. Others have not been so fortunate.

To continue the story, we departed from Dandong and proceeded to cross the river by train across a steel-girder truss bridge known as the Sino-Korean Friendship Bridge. Through the window, I saw another steel-girder bridge running in parallel to the bridge about fifty metres further down the river but when it reached midpoint in the river, it just simply ended except for the remaining spanless piers.

Both bridges were repeatedly bombed by the US military during the Korean War in the 50s; however, only one was repaired leaving the broken bridge as a great location for tourists to gaze as closely as they can into the alien world of North Korea. I was armed with my then UK passport along with my North Korean tourist visa stuck inside of it but with knowledge that I had also omitted the little detail on my visa application that I also held a US passport (left at home of course), it was then that I felt a decidedly uncomfortable feeling of fear and anxiety before the inevitable search and questioning would ensue for each incoming passenger on arrival in Sinujiu. As the train approached and crossed the other side of the river, we could see grey soulless buildings with dark brooding windows gliding by, many of which were adorned with portraits of the Great Leader and the Dear Leader.

The train ground to a halt at Sinujiu as expected at which point we were ordered to leave the train and surrender our passports. Standing stiff and emotionless were ominous-looking officials dressed in black dotted down the railway platform. Military-style martial music was blaring from the station loudspeakers. The music stopped and then our passports were gathered by an official who took them to a building down the end of the platform to be processed. Another official asked me prodding questions about my family life whilst searching through my belongings. He seemed friendly enough but my mind was more tuned into the worry about if they had any means of linking my UK passport to my US one. Not many moments later, we found that a young Irish lad in our group was denied permission to visit the hermit kingdom and had to be sent back to Dandong. Apparently, the reason we were given is that they simply didn’t like the look of him! Anyway, after a little while later and with a great sigh of relief, our passports were returned but to our guide instead and we proceeded with no problem at all to Pyongyang.

I experienced an even greater sense of dread and paranoia when departing North Korea except this was by air from Pyongyang’s International Airport to the city of Shenyang in China. Unbelievably, Shenyang was the only destination on the flightboard inside the terminal building, which was as dead as a mausoleum.

After being seven days within the Hermit Kingdom, the thought had crossed my mind that there could be a possibility that the authorities might have had some time on their hands and the zealousness to thoroughly research our histories. Before exiting the terminal building where our Air Koryo flight was waiting for us out on the apron, we had to present our papers to the last set of officials. At this point, paranoia was setting in and my heart was racing with the possibility that further questioning or even detention could happen should they have found out that I had intentionally failed to provide any information about my dual-citizenship before entering the country. The United States and Japan were, and are still not, flavours of the month in North Korea! Thankfully, it all turned out well and good and I was admitted onto the aging jet aircraft without any problems. I breathed one final sigh of relief when I disembarked the aircraft in Shenyang before heading off back home.

Venturing into the Unknown

Most of us have an appetite to satisfy our curiosity as to what may lie on the other side of something beyond we cannot see. Using the Internet, we can watch point-of-view videos captured by those armed with video and GoPro cameras to recreate some of these experiences; however, it is simply not the same as doing it for real. What makes these experiences thrilling is that there is usually some element of danger or something that could go wrong. For example, exploring an unknown cave armed with a torch and a rope is going to be damned sight more thrilling than ambling along a footpathed cave along with its protective railings located well away from the edges of life-threatening drops and chasms. In an odd kind of way, crossing a fortified international border into unknown territory holds that same sense of thrill and adventure.

If you are interested in viewing my photostory of my trip to North Korea, you can view it here.