There Will Be No More Climbing on Ayers Rock

Shôn Ellerton, June 3, 2019

The sad story when a geological treasure is caught up in superstition, race and politics. All climbers will be banned from ascending Uluru (Ayers Rock) starting from October 26, 2019. There will be more iconic wonders to fall victim to the same irrational reasoning if more of us do not express our concerns.

The Sad News

While listening to the radio in the car the other day, I heard that a 76-year old Japanese tourist died while ascending Uluru (otherwise known as Ayers Rock). The report ended up stating that climbing Uluru will be banned from October 26, 2019. To me, this came as a deep disappointment considering that I, one day, would like to experience the climb and to enjoy that magnificent view of the surrounding outback. Naturally, I thought to myself whilst driving that I better start looking at some ticket and accommodation prices before the looming date while the opportunity still stands. Unfortunately, it seems many others are thinking the very same thing and for a far-longer time than I had. Now, accommodation rates are at a premium due to inflated numbers of tourists who don’t wish to miss the chance. I will probably give it a miss.

Ayers Rock Climb

No pun intended, I had been living under a rock regarding news about the proposed climbing ban so the news came to me by surprise. I was always aware that the authorities discouraged tourists from climbing the rock if they were ill-equipped or not in a condition to do so. Under windy or wet conditions, the authorities close the rock for climbing, which is clearly understandable. I first visited the rock back in 2004 and it was pummelling down with rain. The sight of all the waterfalls flowing down the rock was spectacular indeed; however, I certainly had no intention of climbing a wet slippery rock even if allowed to do so!

Beautiful Waterfalls During Rainstorm taken in 2004

Safety Concerns

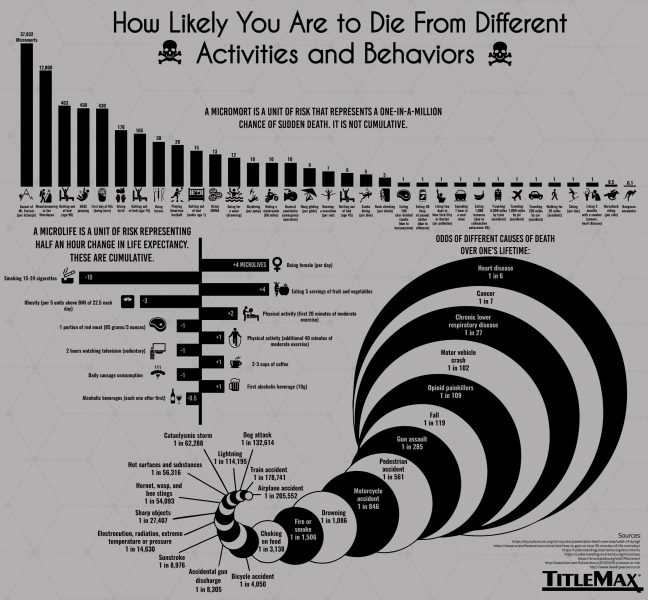

This brings up the issue of why a 76-year-old tourist clearly with a heart condition would be climbing the rock in the first place. Mainstream media raised the news at a high profile, in essence, because of the pending closure of the climbing route and the inflated volume of climbers climbing the rock before the ban comes into effect. It is exceptionally rare for fatalities to occur on the rock. Statistically, one has a greater chance of dying in a commercial jet flying a distance from Sydney to Alice Springs than one climbing the rock. However, statistics can be easily misconstrued of course. Those foolhardy enough to climb a fairly steep rock with poor health or those stupid enough to veer away from the chain constitutes the greatest portion of the statistic. On aeroplanes, this is not the case due to the heavily controlled environment contained within. According to the news, around 37 people have died while climbing Uluru although I have struggled to get a detailed list of who those 37 people were, when they died and exactly how. I later found out that the author of the book A Guide to Climbing Ayers Rock, Marc Hendrickx, managed to identify 18 but, as to the others, information was not forthcoming. From scattered news sources, he identified that 12 suffered from heart conditions whilst the others fell off the rock. As to the timeframe, news sources suggest 37 reported cases from when tourism started in the 1940s. This is an incredibly low statistic. The below graphic is quite informative where one can compare the likelihood of a fatality happening on the rock (which is around 1:500,000) against other various activities. Full image can be found here.

Interesting Statistics on Likelihood of Dying From Different Activities

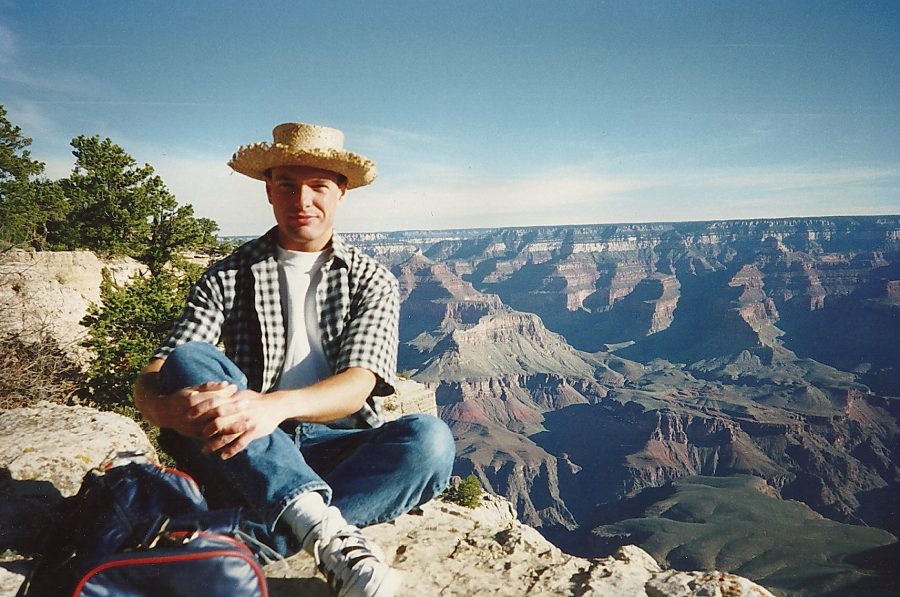

Back in 1997, I hiked the Grand Canyon from top to bottom and back in a day via the Kaibab and Bright Angel trail. I was at the height of my health, had a climbing buddy, started very early in the morning, chose a cooler time of year to undergo the hike and brought plenty of water. We returned back at the canyon rim at 3pm just in time to gorge on a massive steak dinner to celebrate. However, during the walk, we encountered many people really struggling foolhardy enough to undertake the hike in the first place. The canyon claims 12 people per year and airlifts 200 people per year from heat exhaustion or injury. However, comparing the Grand Canyon rim-bottom-rim hike to Uluru may not be entirely fair. The canyon hike is a gruelling all-day affair for most and decidedly dangerous in the height of summer.

Me at the rim of the Grand Canyon during 1997

Perhaps a better comparison is Yosemite’s Half-Dome Hike which has claimed around nine lives of those straying from the cable at the final section since the chain ladder was installed. The difference here, is that, it is quite a hike just to get to the base of the dome section whereas in Uluru, you have hoards of ill-prepared tourists, many of them with young children, having access to climb the rock almost straight away after leaving the car behind. Moreover, to climb Half Dome, one must obtain a permit to do so. The reason is two-fold. Extra funds are raised to preserve the hike but more importantly, the very act of obtaining the permit discourages ‘window-shopping’ climbers; those who casually drive by, ill-prepared, jump out their cars and traipse up the rock, most having no map or any information on what to do in an emergency. Imagine how incredibly low the death count would be on Uluru if you had the same ‘sort’ of prepared hiker that attempts Half Dome.

The infamous cable ladder at final section of Yosemite’s Half Dome

The infamous cable ladder at final section of Yosemite’s Half Dome

Superstition and Photography

However, it’s not really about safety, is it? And this is where I am fearless in writing my opinions and views regardless of collective disapproval, identity politics and political correctness so long as they do not incite hatred, promote crime or induce suffering to others.

I first visited Uluru back in 2004 with a friend of mine who lived in Sydney. I was living in the UK at the time. We did the road trip from Darwin to Alice Springs but ventured the few hours south to visit King’s Canyon and Uluru. At the entrance to the park, we had to fork out $50 (for two of us) to gain admittance to the park. Not terribly expensive and, as long as the fees are put to good use of supporting the park and the local community, I certainly had no issue with it.

Having always had an interest in geology, I was somewhat surprised with the lack of geological information at the park. That might have changed since then; however, most of what we encountered was Aboriginal culture and history. Having not known much about Aboriginal culture, it was interesting to learn something about it; however, we struggled to find much about the geological aspect of the park. If it was there, it was most certainly dominated by the cultural and heritage aspect of the park.

I had every intention of climbing the rock with my friend. He was the same friend who hiked to the base of the Grand Canyon back in 1997 so we had an interest of experiencing an iconic hike to the top. Sadly, it was raining and wet; however, we did have the wonderful sight of having the rock draped in magnificent waterfalls; which meant magnificent photo opportunities. At least we wouldn’t offend anyone by climbing it. But there’s a twist in the story.

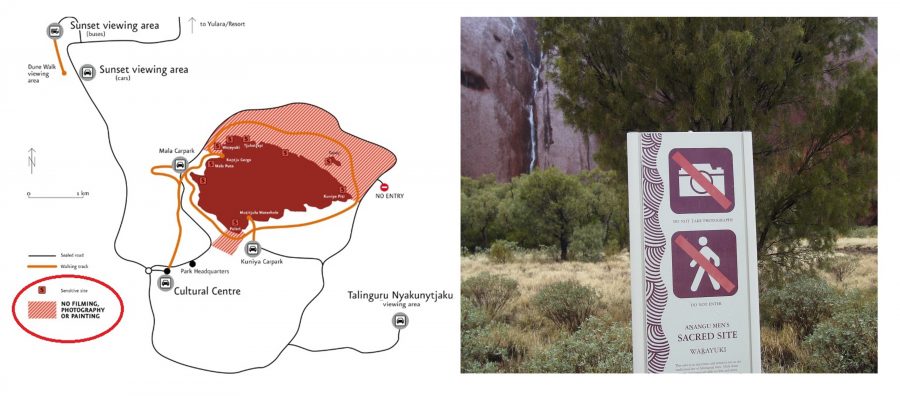

We drove around the perimeter of the rock and I encountered a lovely view of a waterfall descending into the bush at the base of the rock. Being a keen photographer, I got out of the car and snapped a few photos. Only then did I notice a sign NOT to take photographs or enter the area. Having been brought up with a mentality of ‘take nothing but photographs and memories’, I thought this was either a joke or clearly absurd. I took the photos anyway but refrained from walking into the area to get a closer shot. Only much later did I realise that this is a sacred place to the local Aboriginal community. However, I also later learned that massive swathes of the rock are prohibited to photography. Not only was climbing discouraged, but evidently, photography as well. I won’t mince my words here, but this is when extreme superstition and excessive pandering to one collective group is disproportionate, illogical and absurd; especially when many of these ‘illegal’ photo opportunities are yours if you buy them from the local community at the tourist shop in Uluru! I’ve always been wary of taking photographs of people without their express permission, or, at least been very candid about it; however, the very notion of taking a photo of an inanimate object like a rock and being told you are not allowed to because it may offend is farcical.

So not only do Parks Australia intend on banning climbing, but they are imposing more and more restrictions with photography in the park because of superstition. This rock belongs to every Australian, not just one community.

Map showing areas of Uluru where photography is restricted or forbidden

Map showing areas of Uluru where photography is restricted or forbidden

Traditional Ownership

Which conveniently brings me on the subject of ‘traditional ownership’. In the case of Uluru, the Parks Australia website will tell you that the Anangu are the traditional owners and have been there for many millennia ; however, words are carefully chosen because they also state that there is evidence that the aboriginals have been there for at least 30,000 years. Some sources claim that the Anangu were there for 60,000 years while others claim 4,000. These are, of course, gross assumptions. The very term, aboriginal, means indigenous or those living in on the land before the colonists arrived. With over 500 communities each with differing languages, it would be very naïve to suggest that the aboriginals always worked in harmony with others from different communities. It is the nature of our being. We do not always get on. If anything, our current system has improved connecting our aboriginal communities together. If someone asked you who the traditional owners of the European continent are, how would you answer? I have Welsh ancestry and I am aware of the forceful displacement of the druids by the Romans during Julius Ceasar’s reign nearly two thousand years ago but we certainly do not continuously harp on who the traditional owners are. Time is a great healer.

Guilt and Reconciliation

When I first arrived in Australia during the beginning of Kevin Rudd’s reign, I was walking across the bridge over Darling Harbour and saw an aeroplane blowing a vapour trail spelling out ‘Sorry’. I had absolutely no idea why at the time. Only then did it click when I remembered having read something about the Stolen Generations, which must have been an awful time for so many children and their parents. Going back to Europe, there have been countless heinous events spawned from balance of power and differences in ideology and faith most of which have led to severe cruelty and even genocide. There are simply too many to mention. Many of these events are so incredibly recent and yet, many (not all) European countries are making a concerted effort to integrate all communities together within their sovereign boundaries without having to define different ‘playing fields’ for different communities. I’ve never encountered a ‘Sorry’ sign towards any one of these affected communities. Perhaps there are simply just too many of them to focus on just one group.

Skywriting in Sydney on Jan 26th, 2008

The media is intent on continuously reminding us of how we should reconcile and apologise for our colonial ways of the past. Children are taught in school how we should be apologetic for our past actions; that the very land your house is on is, in fact, really owned by the ‘traditional owners’. Being conditioned to feel collectively guilty of something that was done by our forefathers is incredibly unhealthy. We should certainly be taught the facts of what happened with a view to ensure that we avoid committing these acts in the future. We should be looking towards the present and not keep dwelling in the past and continuously reconciling. We will never reconcile or integrate fully if we keep defining different boundaries for different groups of people. Imposing restrictions like banning climbing on Uluru or the recent banning of climbing in a popular area of the Grampians in Victoria is both divisive and disruptive. What has worked so far is the reduction of climbers by discouraging them to do so. In the 1990s, approximately 70 percent of tourists envisaged climbing the rock. This figure was reduced to 16 percent during the last ten years. An outright ban along with the removal of safety chains will only fuel belligerent and unsafe climbing made by illegal climbers, probably made in the safety (from prying authoritative eyes) of darkness. If someone built a church and asked no one to climb it, I absolutely respect that; however, it is safe to say that the rock was there well before the Aboriginals.

How Does the Aboriginal Community Feel?

How do the overall and local Aboriginal communities feel about climbing the rock? Is there any likelihood that tourist numbers could drop as a result of a climbing ban? At the moment (prior to the ban), tourist numbers are absolutely booming, but what about after the ban? 16 percent of tourists who want to climb the rock is certainly a lower percentage than 70 percent from the 90s, but it is still a significant number. Aboriginals have guided tourists up the rock in the past but there is scant media attention paid to it. The first climbing guide was an Anangu man by the name of Tiger Tjalkalyirri who played a vital role in the handback of the rock. He encouraged people to climb the rock. Another Anangu by the name of Paddy Uluru was recognised as the Principal Owner of Uluru until his death in 1979. He stated that the physical act of climbing Uluru was of no cultural significance bar the approach to Warayuki, a Men’s Initiation Cave. Much of what is fed to us by the media has been heavily misconstrued and blown out of proportion by the press. Not much is talked about against the climbing ban simply because doing so will brand you as being brazen, racist, unrespectful and, in general, being a very bad person. We are being conditioned, and very effectively I might add, to fear challenging the subject of such initiatives like the climbing ban.

Local Aboriginal guides

Meanwhile… in Wyoming

Around the other side of the globe in Wyoming within the US is a striking geological feature called Devils Tower. That’s right, the one featured in the 70s sci-fi film, Close Encounters of the Third Kind. It is an impressive geological structure much treasured by the native American community, some of who have expressed their wishes that nobody climbs it. It is also treasured by the climbing community who hold their own spiritual connection with the rocky tower. The United States does not seem to share the same levels of reconciliation and collective guilt as in Australia; however, there is concerted effort to please both the native American community and the climbers without having to resort to outright bans. Native Americans are given additional privileges via the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act; consent to build and operate gambling casinos on their native homeland to raise additional revenue to support their communities. The sad reality is that most of the community still live in dire poverty bar the small number of those who are accessing the casinos’ takings. Defining different boundaries or setting preferences based on a group of people just does not work. In any case, the vast majority of Native American Indians live in cities rather than reservations.

The Devils Tower in Wyoming

Physical and Environmental Damage

From an environmental perspective, issues have been raised concerning tourists that have defecated, urinated and littered on the rock. These should be, indeed, treated seriously just like any other natural wonder of the world; for example, the afore-mentioned Half Dome in Yosemite National Park. Should we ban climbing that as well? Yellowstone National Park is one of my favourite natural spots in the world and I was mortified to find out that rubbish was thrown into Morning Glory Pool, a natural hot spring fringed by a multitude of colours. Do we ban access to these thermal basins and dismantle the boardwalks?

The pristine Morning Glory Pool at Yellowstone National Park

Worldwide, the scaling or climbing of natural and man-made structures are increasingly being made off-limits due to either hyper-sensitivity to superstitional beliefs or from over-tourism which generally lead to higher accident numbers and excessive erosion or damage to the structure. Some have good reason to being made off limits, but many do not.

Angkor Wat, Cambodia and Machu Picchu, Peru

There are many worldwide attractions which are genuinely at risk of erosion and damage. Machu Picchu in Pero, Angkor Wat in Cambodia and some of the old Aztec pyramids in Mexico are features that have been damaged by excessive footfall. The great pyramid of Giza in Egypt had already shut its doors to climbing well back in the 70s due to this threat. But Uluru should not be classed as a feature in the ‘threat of damage’ category.

Other Dangerous and Sacred Sites

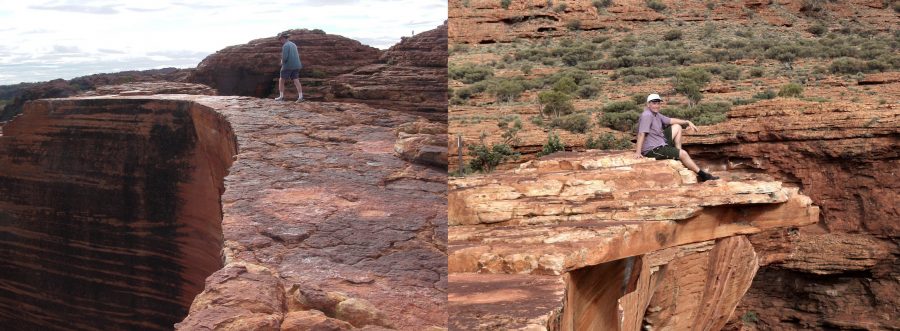

Not far from Uluru is the stunning Kings Canyon. Not surprisingly, many parts of Kings Canyon is sacred to the local community; however, one is still freely allowed to walk in it; at least for the time being. I was lucky enough to explore the canyon during 2004. Casualties do happen here, most notably from the rim walk where one wrong step could be your last.

The majestic Kings Canyon rim walk in Central Australia

Although not sacred, are the great Karri trees used historically as fire lookout towers near Pemberton, Western Australia. Surprisingly, one can still climb these by scaling up the tree using the implanted bits of steel reinforcement spiralling up their trunks; a potentially lethal affair should you lose your footing and slip through the wide gaps between the bars. My wife and I managed to climb one during 2012. After the climb, we were quite surprised that this hasn’t been targeted by the ‘fun police’!

Fire-lookout Karri trees near Pemberton, Western Australia

And finally, Mount Hua in China must be mentioned. China, of course, has a very different standpoint on views of safety; primarily it is your responsibility rather than that of the state. The death-defying ‘plank walk’ around in China, something that would be banned without batting an eyelid in most Western countries looks genuinely terrifying. Mount Hua is very much sacred to the local community; however, it co-exists peacefully with those who simply wish to feel the exhilaration of reaching the top. For some, the very act of climbing Mount Hua is a sacred rite. This is on my bucket list, except, perhaps for the ‘plank walk’!

The death-defying ‘plank walk’ on Mount Hua, China

Generally speaking, if one comes across a spectacular or unusual natural feature anywhere on the planet, it will most likely be sacred to someone.

Conclusion

We all have a variety of reasons as to why we visit such places like Uluru. Some go just to ponder at the wonderful sight from the safety of the ground. Some are lucky enough to be visiting for free as a paid business venture. Some go to visit the cultural and heritage element of the park. And of course, some go for the thrill of the climb, although many who do climb it have expressed that they felt guilty of doing it, but no small wonder considering the volume of rhetoric shoved down our throat by our media.

Take some time to do some research online. Listen to interviews or read accounts by those in the Anangu community. More than four thousand Anangu live in the community, many of which depend on public funding and support by tourism. Many Anangu have no issue of keeping the climbing route open for tourism; they are certainly not unanimous in closing it. To assume that all Anangu have the same beliefs is rather simplistic to say. It is not entirely dissimilar in assuming that all Spaniards are Catholics. Read about similar events worldwide and how the problem is tackled.

For example, how is the Nepalese government handling the debacle that has now unfolded itself with hundreds of climbers queueing up and dying just to get to the top of Everest. Deaths are commonplace and litter by the hoards of climbers have accumulated to high levels. We frown on calling Uluru, Ayers Rock, but most of us seem to have no problem calling the highest mountain in the world as Mt Everest rather than the indigenous Sherpa title of Chomolungma. Everest is just as sacred to the indigenous peoples who live in its shadow as those who reside next to Uluru. It is known by the locals as Miyolangsangma’s palace and playground and all climbers are only partially welcome guests having arrived without invitation. However, much of the community lives off the revenue generated by Sherpas selling portering and guide services to climbers.

Queue of climbers trying to reach the top of Mount Everest

There are two kinds of people. Those who like to climb. And those that do not, or cannot. Those that do not wish to climb or cannot tend to be far less vocal about opposing the climbing ban and often quick off the mark to point out that the rock can be perfectly enjoyed just by looking at it from the ground. However, there are others who have the thrill of adventure and exploration much like the thrill experienced by a child climbing the local playground structure. The press, of course, caught on this analogy swiftly denouncing climbing the rock as akin to being in a playground; an asinine comment if ever there was one.

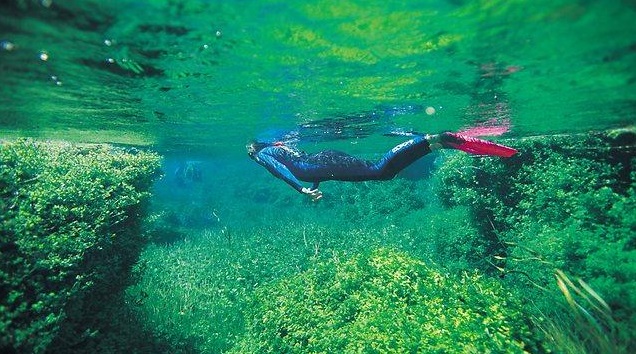

These types of bans only contribute to ongoing differences between groups of people whether they are the Anangu, the casual tourist, the non-Anangu local community and so on. Surely, there must be a smarter way than simply banning the climb outright. Why not adopt a sensible permit system for example and charge a set amount, say $10 or $20 per person? As an example, the limestone ponds in South Australia such as the Piccaninnie Ponds requires a permit to snorkel or dive into. This would further reduce the numbers from the already relatively low number of 16 percent of tourists who wish to climb the rock.

The Piccaninnie Ponds near Mount Gambier, South Australia

Drastic measures such as imposing climbing bans on natural geological features in Australia for the sake of superstition and politically correctness will, no doubt, set a precedent and spread to others. This article hopes to raise awareness that the spread is starting to happen and more of us who want to raise awareness but too afraid to do so from fear of ostracism need to be more vocal on the subject. Thankfully, I have hiked to the top of St Mary Peak in Wilpena Pound during 2009, one of the highest points in South Australia. St Mary Peak is now on the radar of potentially being banned as the Adnyamathanha people view this as a highly sacred place and should not be climbed. This is only one of many potential victims across Australia.

Me and a friend at the summit of St Mary Peak in South Australia

This article could be viewed as some to be offensive or simply an intentional disruption to what we have been led to believe by what mainstream media tell us. However, the intention is to highlight the other side of the story; the side seldom covered by mainstream media constrained by the dark shadow of political correctness. In all such cases, most of the commentary is usually negative for two reasons. First, it is human nature to criticise before praising; of course, there are always exceptions. Second, the fear of commenting in agreement is, itself, open to unwanted negative comments. Not everyone has a Teflon skin! This article is open to commentary; however, comments which are made anonymously, expletively and with no basis-in-fact will be duly ignored. If I have missed something or there is an aspect that I did not mention in the article or if I have simply offended the reader, not someone else, feel free to comment.