Could English Become the One Surviving Language?

Shôn Ellerton, December 10, 2019

Is it possible that, sometime in the future, all other languages will die in favour of English?

Could there be a day in the future when the only language in the world that anybody speaks is English? I’d like to think not, however, it is a fact that English has been increasing in dominance globally with respect in being the de-facto regular working language.

A very large and fast-growing vocabulary

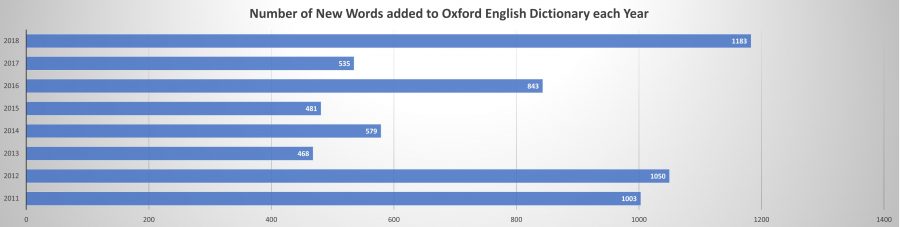

English has been heavily bastardised and expanded upon throughout the centuries adopting a myriad of new words each year many derived or taken directly from other languages. That’s not necessarily to say that English has the most words of any language, but at over 600,000 words, it is certainly truly impressive. According to the OED website, between 500 and 1000 words are added each year to the unabridged Oxford English Dictionary, traditionally an enormous 20-volume collection of hefty tomes comprising of more than 20,000 pages of words but now, of course, available for all in electronic format. With English becoming ever more popular worldwide, it is not surprising that English has been widely adopting foreign words for many decades or even centuries. This, of course, makes English a very rich and diverse language, but let’s not delude ourselves into thinking that it is the most diverse of all languages.

English is not necessarily the most diverse language

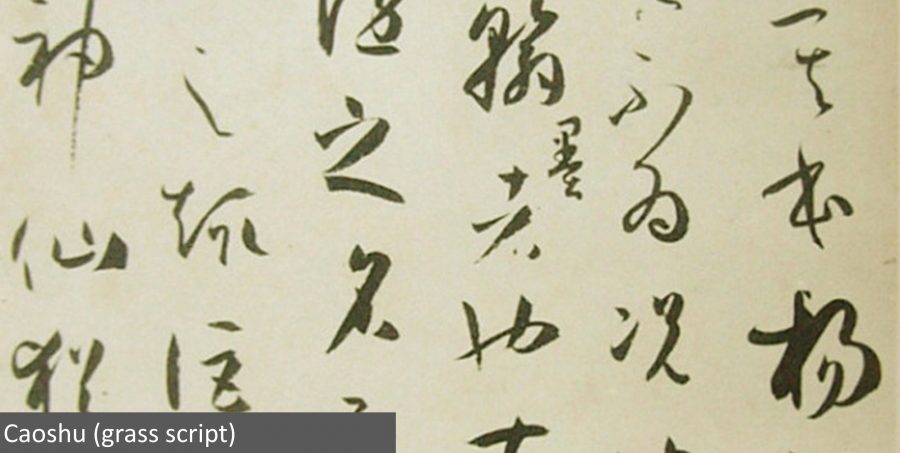

Allow me to digress for moment. Many native English speakers take pride that English has the richest variety of words and expressions; however, many other languages are incredibly rich and complicated in their own ways. Take Chinese for example, a language with a vast quantity of pictorial characters, many of which are virtually never used. The average person in China probably uses no more than 4,000 characters; however, Chinese operates very differently from English. Most words are formed using a combination of two or more characters. Moreover, Chinese is famous for its 4-character cryptic idioms called chengyu, which are often used in Chinese poetry and, on a personal note, are beautiful and elegant. These are often used in everyday conversation and, unless one knows its meaning, they are virtually indecipherable. If you ever looked at a document or item with multiple languages such as an airline safety card or an immigration form, you might notice that Chinese is usually the shortest of the translations, which usually makes it more difficult to translate into English due to its terseness. Chinese is one of the few languages where shorthand is not necessary as one can write as fast as one can talk using the beautiful but difficult-to-read grass script. I struggled taking three years of Mandarin evening classes only to then find that I can barely muster a simple sentence using the most common of characters.

The challenge of learning a foreign language in an English-speaking environment

Studying a foreign language is very rewarding although, for some, a difficult and challenging experience as it is for me. The writings of foreign language are also often beautiful. The sumptuous flow of Chinese calligraphy and the elegance of Arabic script is artwork in its own right. Having a German mother, a Chinese wife and a French stepfamily, I should be fluent in German, French and Mandarin, but alas, I am not. The problem for many English speakers, as in my case, is that it is incredibly difficult to learn a foreign language whilst living in an environment where so many speak English. For many, it takes a high level of discipline and immunity from minor embarrassment to speak in a foreign language if everybody else can speak English.

My wife and I, on occasion, host international students; usually two at a time and usually of different languages. They are immersed, at the house and at school, deep into English. They need to speak to each other in English and they need to listen to classes in English except when they are speaking to their parents and friends from home on their mobile phones or computers. Reciprocating exchange students from English-speaking countries sometimes do the same; however, exposure to English is far more likely making it more difficult to be fully immersed in the foreign language.

Reports and articles in the media come up from time to time reminding those living in English-speaking nations that our level of foreign language skills is far less than those from other nations. I remember reading an ERASMUS report how students in English-speaking nations have the lowest score with regard to the percentage of the student population willing to learn a foreign language. What the reports do not state is what percentage of students are willing to learn a foreign language other than English. The reports often spin the story to point fingers to the inadequacies of how native English speakers are not willing to learn a foreign language or are too lazy to do so.

English as the de facto world language

The reality is that English is fast becoming the de-facto world language. Some may dispute this on grounds of being non-diverse, non-accepting, or simply not being respectful to other cultures and languages. They may do so, but the facts state otherwise. As of writing, it is reported that 1.5 billion people speak English of which only 360 million are native English speakers. That’s 20% of the world population. Moreover, many non-English-speaking nations teach English to school students as a mandatory subject, for example in many countries of Europe including all of Scandinavia plus many of the Arabic-speaking countries. With respect to reports outlining the performance of native English-speaking nations scoring lower than others on learning a foreign language, this speaks for itself.

Let’s not forget television, movies, music and the viral spread of social media. As far as I can remember, all English-speaking movies and TV programmes in Scandinavia are subtitled in English. In contrast, France and Germany, to name a few, still stubbornly hold on to the practice of dubbing, a practice many proclaim, to be protecting an ageing industry. It is no wonder that Scandinavian children learn English far quicker than their French or German counterparts. English-speaking music and film, undoubtedly, dominates partly due to the power of online distribution, notably that from social media, and the amount of spending incurred to create them within wealthier nations. I’m not saying that other non-English speaking nations don’t create an abundance of music and film. Far from it. For example, Bollywood, India’s answer to Hollywood, is known for its vast production of movies, although seldom do they make popularity outside of India’s borders. It’s far more likely that the latest Star Wars movies will penetrate to virtually every country on the globe than the latest Bollywood blockbuster.

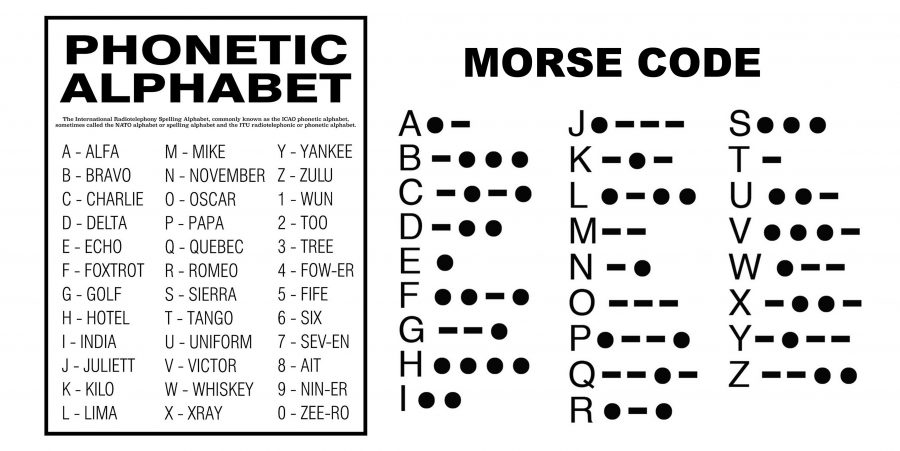

English has been accepted as the universal language with respect to international aviation, radio telemetry and marine navigation. All acclaimed radio operators will know of the International Radiotelephony Spelling Alphabet and its associated Morse Code. A is for Alpha, B is for Bravo, C is for Charlie, and so on. One of the leading successes of the English language can be attributed to its use of the Roman alphabet, a relatively easy script to write. Practically every keyboard and device use the Roman alphabet. There are odd differences, for example, the layout of a French keyboard, but generally, they all share the same universal layout. An array of interesting Chinese keyboards still exists but with the advent of Pinyin and other systems of Romanising the Chinese script, they are fast fading away. Most Chinese tend to use standard QWERTY keyboards with some keyboards having keys shared with common Chinese character elements.

Esperanto, a failed attempt at a new universal global language

Going back to my childhood when visiting my German grandfather, I had many very interesting conversations on science and language with him. He was, what many would call, a ‘hard’ scientist; logical and sceptical. There was a physical answer to everything. Moreover, he absolutely loathed politics and couldn’t care a stuff about the subject of religion, superstition and fiction of any kind except for, oddly enough, the TV series, Doctor Who. I told him that I was learning German at school to which he responded that I was simply wasting my time. ‘Pah! Wait 20 years and, I assure you, everyone will be speaking English anyway.’ Coming from a man who advised his own daughters not to use X-ray shoe machines (popular in the 60s), to show how your feet are fitting in a new shoe, I always listened to what he said with credulity. I then asked him what ever happened to Esperanto, a new language developed in the 70s to bring in many of the European languages together to create one universal language. His reply was comical, surprising and possibly very correct. ‘Why would anyone speak a language you can’t swear in. Esperanto died before it was born!’ I’m quite certain that this is not the only reason for Esperanto failing but it holds plausibility as Esperanto, indeed, was built without swear words. Regarding his predictions of English killing off other languages, it hasn’t come true, at least, not yet.

Without swear words, no language is complete!

Conclusion

I’ve always held a fascination in the study of foreign languages. One of the most interesting books I’ve read is a book called The Languages of the World by Kenneth Katzner. More than 200 languages along with their native scripts are briefly described along with a translated passage for examples. Some of the languages include Native American languages which are deemed to be some of the most complex every devised. Our multitude of languages make our world a more interesting and colourful place and I personally hope that we don’t eradicate them all. I’m not suggesting that we should practice the expensive outlay of providing dual-language signage just for the sake of preserving the language. That is an artificial method of attempting to preserve a language often at the expense of the taxpayer. Look at the dual road-signage in Wales, a country where the north and the south disagree on half of their own language!

With the rise and power of social media giants and the vast quantity of material in English online, love it or loath it, English is steadily creeping to true dominance. Those who are not raised in a native English-speaking country are practically obliged to learn the language to make a successful path into our increasingly global economy. English, to some extent, is like Microsoft, a software company that has practically killed off its entire competition.

Many languages have become extinct or becoming extinct, for example, Cornish and Breton to name a couple of Celtic origin and many other indigenous languages of Australia and the New World.

Back to the original question. Could English ever be the only surviving language left? I don’t think so, at least not for a very long time, if ever. It’s more likely that we’ll eradicate ourselves by other means beforehand! The truth is that many of us are in favour of preserving our variety of languages giving us a rich and diverse society in which to live in and explore.