Railways Are Not Supposed to Make Profits

Shôn Ellerton, January 10, 2020

Our railways should not be focussed on greed, profiteering, cost-cutting, and relegation of responsibility to the private sector. They are there for the greater good.

I’m lucky and fortunate enough to be within five minutes by foot to my local metro railway station in Adelaide. It takes me right into the heart of the city in less than thirty minutes stopping only twice if I take the express. It’s clean, comfortable, free of vandalism, electric, air-conditioned and, usually, on time. Some of the other railway lines are yet to improve, but hopefully it’s only a matter of time when they get revamped.

Clean, comfortable Adelaide Metro electric train at Hallett Cove

During a New Year’s party at a friend’s house, I started talking to a guy called Bruce who works for the Adelaide Metro as an electrician. He started to talk about the future of the railway, how the metro is making a loss and the likelihood that it’s going to be privatised. The words ‘privatised’ made my heart sink. Undoubtedly, if that happens, the railway will deteriorate, services will be cutting, prices will go up. After all, as a private business, it’s all about money, money and money. Gotta be in the black!

As for making a loss, well, heck, isn’t that what metro municipal railways do anyway? Why do we have to make a profit out of everything? There are a few exceptions in which some railways do make a profit but the vast majority of them simply do not. And are not meant to.

Railways are for the greater good

Why do we have national railway networks? I’d be insulting the reader’s intelligence if I had to explain the obvious reason, that people need to get in and out of the city to work, amongst many reasons. For those of us that have tried to commute in a heavily congested city when public transportation is on strike, many don’t even bother trying to get to work at all. The roads are impossibly jammed and even if one manages to get to work by road, there’s usually no place to park.

When public transportation isn’t working, whether it is due to a strike or some other event, the city virtually stops working, only running on inertia or from the very few who so happen to be situated within walking or bike distance. The overall revenue and productivity generated by business in the city starts to drop precipitously. Industries where workers can perform their duties from home, for example, within IT and project management, may not be as greatly affected. However, the cumulative effect of high productivity has a positive effect on the nation’s wealth, of which, a portion of that extra wealth is put back into the public purse, some of which is used to pay for the metro system.

I fail to understand why it’s so important that national railways need to be self-sustainable and profitable. It’s not like running a restaurant or a retail outlet where making a profit is critical in keeping the business alive. When a restaurant or retail outlet fails, the premises are laid vacant waiting for another business to give it a ‘go’ at it. What happens when railways don’t make a profit and go into the red? That’s right! You’ve got it! The public bails them out while the fat cats at the top take the cream off! Seriously, what the hell?

How to quickly deteriorate a train service

It never ceases to amaze me how decisions come about to privatise national rail networks in the first place. I lived in the UK during the 90s, a time when British Rail was being carved up into various private operators running on infrastructure having been privatised into Network Rail ownership.

During this period, I noticed how the railway service deteriorated. During the late 80s towards the middle of the 90s, I often took the train from London Euston to visit family who lived in a little coastal village called Llwyngwril in Wales along the picturesque Cambrian Coast line. At first, it used to be a comforting, fast and relaxing way to get there but that was no longer to be.

During the 80s and possibly into the early 90s, I could take an Intercity 125 train all the way to Llwyngwril. It was a proper train consisting of more than ten carriages with a restaurant car, first, and second-class facilities. It was quiet, smooth and comfortable in the passenger carriages and fully air-conditioned. As a bonus during weekends, for a small £5 supplement, you could go into first class! I could get onto the train in London from Euston terminus, find a comfortable place to sit, and not have to move out of my seat until the train took me directly to that little village lying so peacefully between the blue waters of the bay and the emerald-coloured hills strewn with sheep. It was surreal that a train service could start off amongst the throngs of crowds from the station platform in Euston, London and a few hours later, end up in a serene and quiet location with the freshest of airs. After this point, the train then continued to meander peacefully along the coastline passing through beautiful Barmouth and Porthmadog ending up at the little windswept town of Pwllheli nestled at the north end of Cardigan Bay. For those of you into travelling scenic railway lines, this is worth going on.

Not long after the knives of privatisation started to have an effect, the direct service got shortened to a little town in central Wales called Machynlleth, where I had to change on to a horrible little contraption called a Sprinter, basically an excessively noisy exceedingly uncomfortable diesel-driven railcar with terribly bright fluorescent interior lights and nasty hard seats. Bright interior lights are a real pet hate of mine as you can’t see anything out of the window when it’s turning dark except a reflection of yourself. The nice Intercity 125 train I had to alight from continued along its merry way towards the nearby terminus of Aberystwyth, an attractive university town in the middle of Wales along the Cardigan Bay.

The dreaded Sprinter railcar

Not many months later, the once-admirable direct service to Machynlleth died. The service was then curtailed terminating at the English city of Shrewsbury, where I had to change on to a Sprinter in order to continue my journey. I had to change again at Machynlleth.

And again, after that. The Shrewsbury direct line ceased as well having to make do with a direct connection to Wolverhampton or Birmingham New Street and then change again onto two or more sprinters to get to my final destination. So basically, I ended up spending most of my time cooped up in these dreadful Sprinters.

Ticket prices went up considerably higher too, certainly not in line with inflation. It was no longer a comfortable and enjoyable proposition to take the train either, so I did long night drives when the roads were clear of traffic. At least I could sit in the same seat!

What made the train a pleasure to use turned into a stressful grind of having to make connections on time, deal with seat changes, and endure journeys that took far longer than they did before. Not only that, nobody really knew when the trains operated because the old national British Rail timetable everybody was used to was replaced by a confusing array of timetables published by various train operators.

All for the sake of cost-cutting! Privatising national rail networks basically sucks.

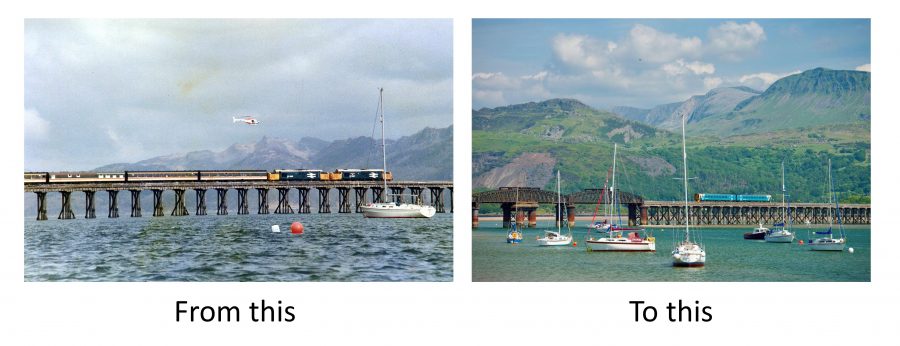

Below is the magnificent Barmouth Rail Bridge.

How many people can we stuff on a train?

Back on April Fools’ Day in 2017, I wrote a fun article about British Rail’s Secret Scheme Finally Being Revealed. It looked serious enough at first glance, but it was a complete piss-take. However, I did include in that article something which is inherently true once private companies get their paws on public services. They want bums on seats!

The beauty of taking the train, unless it’s at peak hour during rush hour, is that you’re going to get a seat unless you’re exceedingly unlucky. If you’re taking the train from London to Edinburgh, you want a little space, don’t you? You know too well that you probably would have been able to get to Edinburgh cheaper and faster by flying but you decide to saunter through the countryside in pastoral style. Perhaps to enjoy a beer or a glass of wine, munch on a fruit cake and watch the sheep and cows slip past your window. You could be travelling alone and have a whole window bay with its own little table to yourself. After all, there’s plenty of space for all.

That’s the problem right there. The companies who own the service don’t like this. They view the vacant seats on the train as lost revenue by deploying too many carriages. Money could be saved by removing a carriage or two.

Roll on later after the numbers are crunched and the service now runs with two carriages less. The train feels decidedly more cramped and crowded. You’re now sitting with a couple of backpackers scurrying away in their rucksacks looking for nuts and muesli bars and you’re jostling for elbow room as their rucksacks collapse into your seat space. You don’t feel relaxed at all. You’re just hoping that they’re going to get off on the next stop, but you silently gasp in horror and resign in defeat when the ticket collector comes around and says, ‘All the way to Edinburgh I see!’ You desperately look for more space, perhaps eyeing up ‘next stop I’m off’ candidates. All in all, you end up driving or taking the plane in future.

The train operator notices that there are less bums on seats again and perhaps take it as a sign that the service is not needed as much as it was. So, what happens? They remove more carriages and/or make the services less frequent.

This goes on and on until, ultimately, the locomotive-driven train is replaced by a set of railcar units with one or two carriages in operation, or worse, the service is discontinued.

Railways do not make money!

Railways are expensive. There’s no getting away from it. Anything to do with railways costs a lot of money. I’ll give you a little example from my family experience that owned and ran a narrow-gauge steam railway. We relied solely on tourists during the short holiday season and help from volunteers. That was our only income. There was no access to public money and government grants were very difficult to obtain.

My family, back in 1983, decided to purchase and run the Fairbourne Railway, a 3-mile-long tourist narrow-gauge steam railway in Wales. It was a very poor financial decision, but I was too young to have any say in it. It did; however, teach me many new experiences in the running and rebuilding of a railway. Anyhow, we sold it during 1995 and let me tell you now. A lot of money was spent on it and, presto, we never got out of the red. We even transformed the railway beyond recognition (much to the dislike of the original volunteers of course) earning the prestigious Prince of Wales Award. Tourists certainly arrived at greater numbers than before, but by then, cheap overseas travel and a series of not-great summers had become prevalent and tourist numbers dropped in subsequent years.

We marketed it alongside British Rail. We even struck an arrangement with British Rail for punters to take the steam train and little ferry from Fairbourne to Barmouth and return via British Rail across the estuary bridge. They helped us market the attraction and yet, we still could not keep afloat. There’s a little more to the story than this of course but one thing we knew for sure. None of the other narrow-gauge steam railways in Wales were profitable either, bar one or two. Most of them had received government grants but we did not. Only two became profitable in the end; the magnificent Ffestiniog and Welsh Highland narrow-gauge railways thirty miles north of Fairbourne. They are still running quite successfully today.

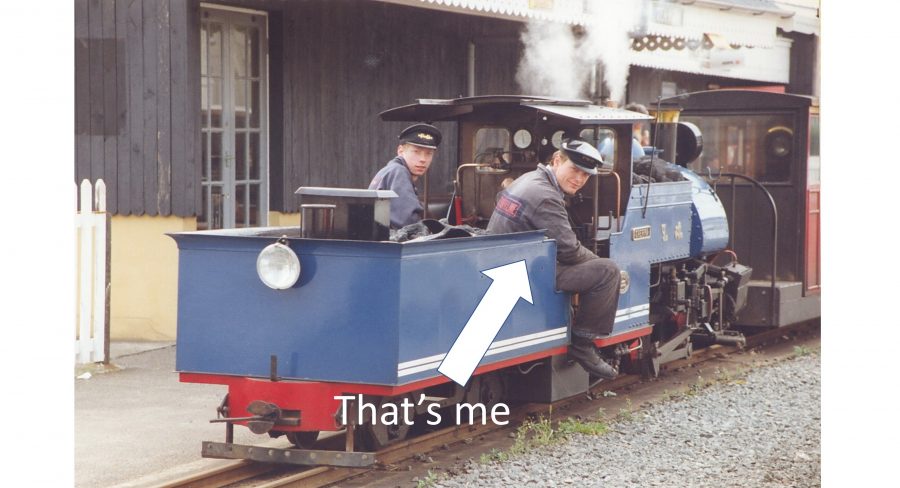

I know a few things about railways. I lived and breathed them during my childhood and young adulthood. I built track, ran operations, drove steam and diesel locomotives, helped with track maintenance, and so on. We also had volunteers and staff who still worked or retired from British Rail, so we had a great deal of knowledge from them as well.

Sherpa, half-size Darjeeling steam loco with me driving it

Later in life as a graduate civil engineer, some of the first jobs I had, included the design of railway infrastructure. Coupled with my experience with the family business, I had a reasonable understanding of the costs of running and maintaining railway networks. Without volunteers, maintaining and running an independent tourist steam railway would have been near impossible. Then there were the dreaded visits by the official track and boiler inspectors which usually meant more money spent on deficiencies to be rectified.

It goes on. The high cost of utilities including the ridiculous battle we had with the water company suggesting that we need to pay more for the sewerage because we used so much water. We eventually ‘educated’ the utility company that most of the water used went up into the atmosphere as steam! And of course, the constant wear and tear on building structures and motion gear due to the howling horizontal winds strewn with dune sand. Then you had to pay the working force including the expensive precision engineers who ran the lathes and milling machines. I could go on and on.

In the world of standard gauge and public railways, staff need to be well trained and paid accordingly. Again, once private operators step in, wages get cut and short cuts are taken. One only needs to look what’s going on with the shortage of decent pilots flying domestic routes within the United States. Some of them are struggling to meet bills on the salaries they are getting.

In a nutshell, railways do not make money, except under special circumstances.

Railways that do make money

There are railways that do turn out profits, but they are far and few between. Some comprise of popular tourist railways, although most do not as they are at the mercy of the tourist and off-seasons. Others who do well include independent operators that have exclusive access to a much-needed service, for example, airport services, or of those operators that have a monopoly of a very busy metro area with near-continuous full carriage occupancy. Those operators that may have exclusive control of a regional area in the middle of nowhere after being carved up by privatisation deals, tend to rack down their services to the extent that no one really wants to use or rely on them anymore.

This is the biggest issue with selling off chunks of the national railway system to private operators. The rural and regional railway services die a slow death which stifles industry and growth in locations away from the bustling cities. This has a snowball effect of more and more businesses locating in already overcrowded cities because more people are moving to them due to less and less jobs being available in regional or rural areas. And of course, the house prices…

The whole point of making profits in the busy and profitable areas is to give assistance and much-needed funding to keep the rest of the national railway working and to encourage businesses and industry to move out of the most popular cities. This just seems so obvious and logical to me.

Conclusion

I can’t possibly cover every exception to the rule on those railways that do make money or of those railways that have done well under privatisation. It’s common knowledge that the British privatisation of their railway network has been nothing short of a disaster. Billions of pounds have been spent from the public purse to bail out the companies that own the rolling stock services and the infrastructure. Ticket prices have jumped astronomically. According to the Independent, ticket prices have generally jumped three-fold since 1993.

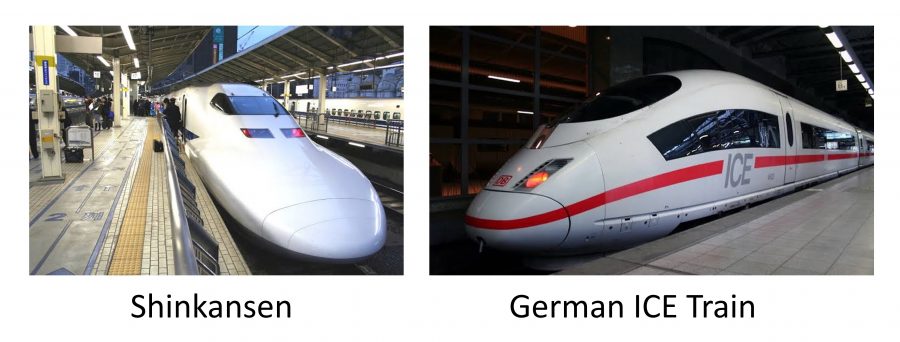

Other countries that might have adopted a more successful privatisation plan of their rail services include Japan with their so-called ‘JR’ companies controlling different regions of the Japanese network. I have read reports that this model is showing some signs of stress and not working as it once did. What is undeniably true is that their bullet-train service (the Shinkansen), has been an attributing factor to the success of this model. Britain, of course, does not have any service remotely geared to high-speed except for, perhaps, the London to Edinburgh route.

The German model is interesting insofar that operators and infrastructure are controlled by various companies. According to one source I read, under EU law, ownership of operating services and infrastructure must be separate. But this is the thing. The shares of all these companies bar a very, very small percentage is owned by the German government. Which means, essentially, the German rail network is nationalised.

The underlying motive for most governments to sell off national assets is to rid themselves of the responsibility of maintaining them. This of course, begs the question, as to what purpose the government is there for with respect to providing the services the public needs for the greater good. One could argue that private companies need to pay their way, but inevitably, much like major banks, national railways cannot fail. They are usually, in the end, subsidised with even more money than before from the public purse after the profits have been decanted into the hands of those sitting at the top.

There are some that compare the model of privatising railways against that of the aviation industry. However, that’s not a fair comparison. Airline routes don’t share permanent way (tracks, signals, crossings, etc) infrastructure but rather, share airspace with other airline operators. There are some that protest the idea that the public should be paying for a national rail network, particularly from those that don’t use them. They tend to forget that privatised networks are usually subsidised by the public in any case. And yet, we spend national money on defence, education and health. Moreover, they dismiss the benefits what a national rail network can do to bring more business into areas benefiting even those who never use the trains.

I am a firm proponent that national railway networks should remain in the hands of governments, much like some of our nations’ mail, defence, education and health systems are.

Railways are not meant to make money but rather, to serve for the greater good by promoting business, industry, environment and, in general, a better lifestyle for all. In sum, taking all these factors together, the nation becomes a wealthier place.

~

As an addendum, should you be interested in seeing photos of the Fairbourne Railway during the Ellerton Era, here’s the link.