Here’s a list of some of my favourite piano classical pieces in no particular order as the list is growing.

Opus Clavicembalisticum (1930) – K.S. Sorabji

Piano Sonata No.1, Op.12 (1926) – Dmitry Shostakovich

Piano Sonata in B minor, S178 (1852-53) – Franz Liszt

Ballade in G minor, Op.24 (1875-76) – Edvard Grieg

Trois Etudes de Bravoure, Op.16, 1st Etude (Mouvement de valse) (1837) – Charles-Valentin Alkan

Vers la Flamme, Op.72 (1914) – Aleksandr Scriabin

Opus Clavicembalisticum (1930) – K.S. Sorabji

This rather-sounding bombastic title in Latin simply means ‘a piece for the piano’. From what I’ve read, Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji (1892-1988) of British origin is described as being ultra-reclusive, highly intelligent, arrogant and of a predominantly disagreeable character. Many of his pieces of work are so insanely complex that only a handful (literally) can or have been able to play them. He refused to write finger notation as he believed anyone who has the audacity to play his music would know what to do with their fingers. He detested the thought of anyone playing his music ‘badly’ or not to his satisfaction and went so far as to ban anyone from playing his music in public unless they had his permission to do so.

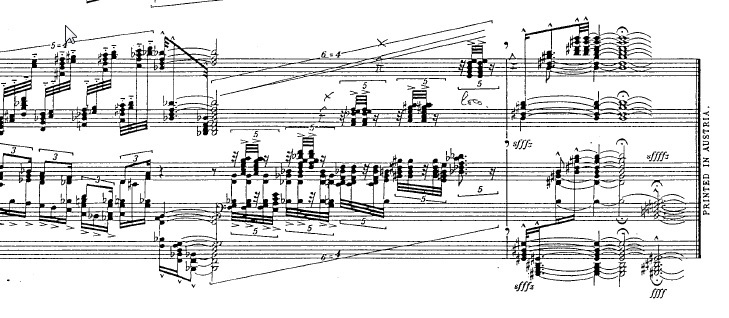

The Opus Clavicembalisticum (O.C. for short) is such a piece. It takes a mind-boggling 4-5 hours to play the whole piece (and that’s at a pretty fast pace I can tell you!). There are 13 sections of the piece covering 252 pages of music manuscript. There are passacaglias, fantasias, cadenzas and four extremely complex fugues. Most of the music needs to be written on four staves in order to be read without clutter (or less of it!).

Only two pianists have recorded the O.C. commerically to my knowledge; one being John Ogdon and the other being Geoffrey Madge. As well as Sorabji, John Ogdon’s life seemed to be equally interesting (and tragic). After reading his story, you can almost deduce that you need to be somewhat insane to be able to play the O.C. It is well worth the read. Being a pianist (not a particularly good one), I enjoy following the scores of the music but it’s a real struggle to keep up with the O.C. with it’s devil-like speed and ferocity.

When you first embark on the journey of listening to the O.C., the piece starts with a solemn graveness and gravity and maintains to do so for the entire length. It is dissonant like much of the classical works being composed during this time. There are exceptionally fast-flowing passages, slow moments, powerful chord passages of the utmost complexity but never does this piece show any sign of being lighthearted or happy. I consider this piece of music to be amazingly beautiful but it is also exceptionally dark and sinister with the sole purpose of exhausting the performer (and the listener).

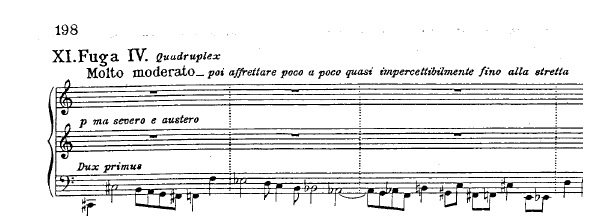

I found the last part of the O.C. the most interesting. This starts at Fuga IV and continues to the end of the O.C., although technically, there is the Coda Stretta which covers the final few pages but I always believe that the Coda Stretta is really the last bit of Fuga IV.

Fuga IV (including Coda Stretta) is, itself, nearly an hour long (the last 3-4 minutes being the Coda Stretta, perhaps the ultimate ending of any piano piece I’ve heard). This piece starts slowly and deliberately with a common recurring theme as a fugue would traditionally do. This recurring theme can be played by simply playing the first three measures below. When hell breaks loose and the piece goes into a frantic pace, you will still pick up this recurring theme now and again.

Fugues can be highly complex, and in this regard, Fuga IV reaches into the stratosphere. Not that I’ve played it, but the notorious Hammerklavier Sonata by Beethoven seemed to pale into insignificance after listening to this. The ending (if you get there) is mesmerizing and cataclysmic and will leave a lasting impression (if you’re into this sort of music).

Piano Sonata No. 1, Op.12 (1926) – Dmitry Shostakovich

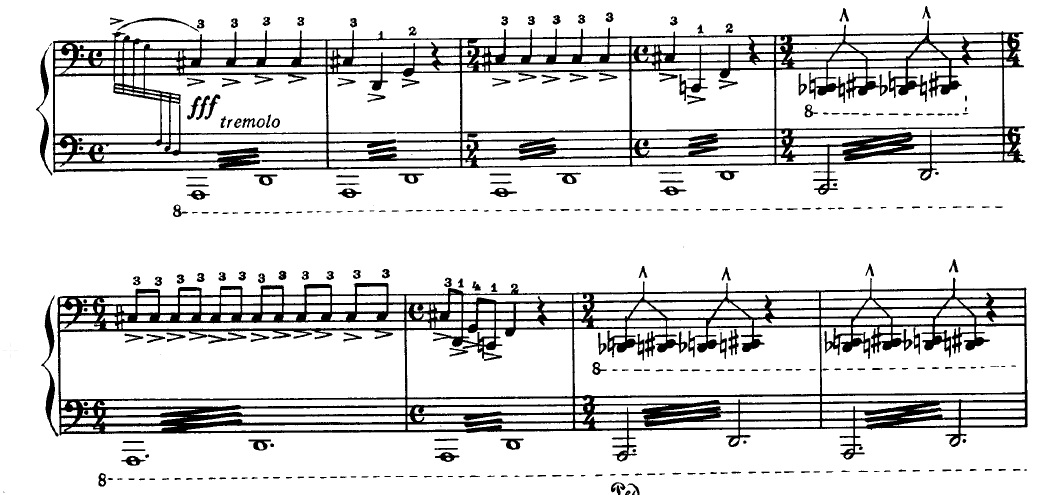

This one-movement sonata by Dmitry Shostakovich (1906-1975) is a bit of a roller-coaster ride indeed! This dissonant and complex piece of music is both exhilarating and haunting and amazingly, it was written when he was only 19 years old. Whatever was on his mind when he wrote this, he certainly wrote a very interesting piece indeed. I’m sure that some of the style of the sonata may have been influenced by Prokofiev’s later piano sonatas, most notably the 8th.

Generally speaking, it can be largely divided into three parts. The first part is fast and complex and ends with the a slow ominous passage (see illustration below). This young 19-year-old must have had some dark thoughts when he wrote this.

The middle part is my favourite. This part constitutes the slow quiet haunting part of the sonata. It crawls on you in a very creepy way.

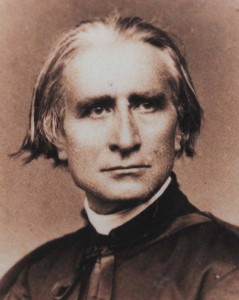

Piano Sonata in B minor, S178 (1852-53) – Franz Liszt

If there is to be a perfect classical piano piece which embodies the spirit of the piano, I would rate this piece very highly. Unlike the first two pieces on this list, it is accessible for most, if not all, listeners. It also captures just about every type of mood, from lyrical and beautiful to mysterious and ominous to majestic and powerful. This nearly 30-minute one-movement sonata (the only one Liszt did) is epic and requires a high-degree of skill and stamina to play.

Liszt (of Hungarian origin) composed a vast number of pieces in his time and is known for being the first to play solo in virtuoso recital form for the piano. He was known to be a highly charitable person and always showed appreciation for other composers during his time. During his years as a concert pianist on his ‘roadshows’ through Europe, he was considered to be the ‘rockstar’ of his time from his vivid and wild performances. During his later years, Liszt encountered various family tragedies and became more and more obsessed with the darker side of life and preoccupations with death. His later pieces are generally quite dark, with some setting the scene for being the precursor of contemporary classical music.

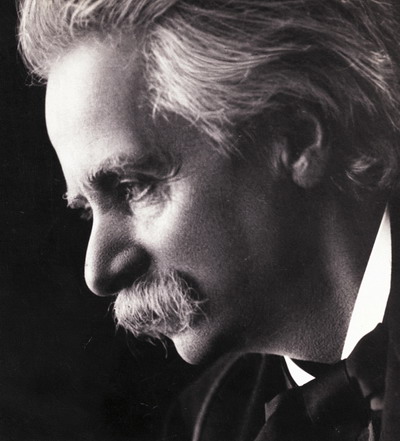

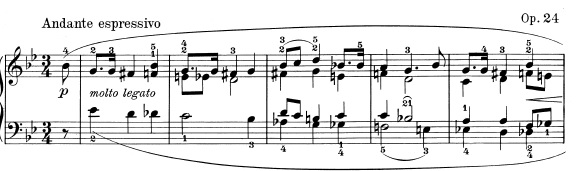

Ballade in G minor, Op.24 (1875-76) – Edvard Grieg

This Norwegian composer is mainly known for his magnificent Peer Gynt Suite, which includes the very well-known In The Hall Of The Mountain King score. What isn’t so well-known is his amazing Ballade in G minor. This 20-minute complex piece of music packs so many emotions making you think that this could have been written by someone who had an adventurous life but, somehow or another, lost everything and in Pythonesque parlance, is really ‘pining for the fjords’ and the peaceful beautiful solitude of his homeland. This piece of music is beautiful to listen to; however, there are passages which are so full of desolation and despair, it would be hard not to shed a tear or two.

The general pattern of this piece starts with a simple sad melody which then erupts into various themes ranging from quick and playful to devastating and sombre. In particular, the middle Lento passage is quiet and very very mournful indeed. After this middle passage, the ballad heats up with flavours of Russian and Hungarian folklike themes ending up with a crash-like chord finally ending up with an even sadder reprise of the first passage of the ballad.

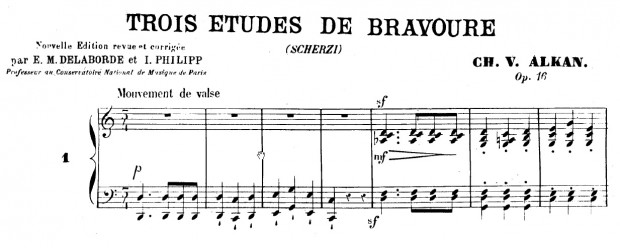

Trois Etudes de Bravoure, Op.16, 1st Etude (Mouvement de valse) (1837) – Charles-Valentin Alkan

Poor Alkan never really got the recognition he deserved. A Jewish Parisian during the times of Liszt and Chopin, this rather reclusive and shy character created some outstanding material, most of which is generally unplayable by most mortals. Interestingly enough, Sorabji himself, was one of the first to really promote Alkan’s works and lift his name out of obscurity. Even Liszt, a very modest and charitable individual, openly declared that Alkan’s works are superior in form and composition than his own.

I have not had much experience of listening to Alkan’s works; however, I was struck by the first etude (or scherzo) of his Trois Etudes de Bravoure. Actually, it is really the second (or middle) part of the first etude which is what is particularly interesting although you need the first and last parts to complement it.

The first part of this etude opens with gusto and action.

And there it continues until the middle passage is reached.

This quiet section has a precise tick-tock rhythm in the bass and a light lyrical musicbox-like theme which becomes progressively more complicated. Moreover, the melody seems to get somewhat ‘distorted’, as if everything is not going quite right. Oddly, it reminded me of the murderous puzzle box in Clive Barker’s film, Hellraiser, in which a little tune played but very much out of tune, until, of course, the puzzle box opened and claimed its victims! In any case, it is an interesting sequence

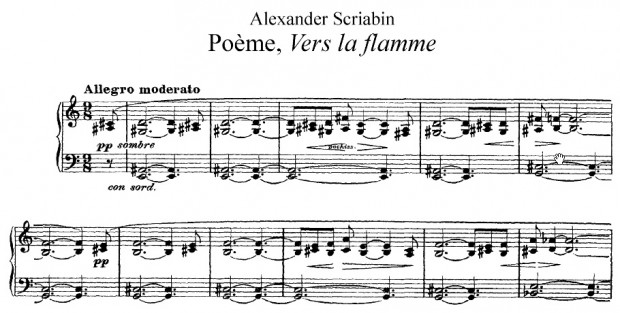

Vers la Flamme, Op.72 (1914) – Aleksandr Scriabin

A Russian great, alongside with Prokofiev and Rachmaninov, Scriabin may not be as well known but his music is something to experience.

Vers la Flamme (Towards the Flame) is a piece of music I instantly liked due to its mystique and complexity. It has a beautifully contemporary feel much akin to walking into a space developed by Frank Lloyd Wright or from Ayn Rand’s fictional architect in The Fountainhead.

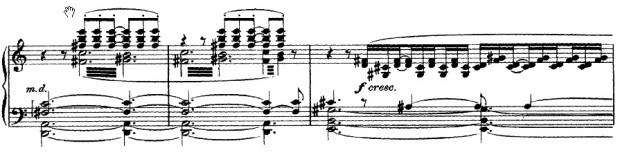

The piece starts off very slow and somewhat foreboding, but begins to build momentum by introducing rolling arpeggios and throwing in accented notes in the upper register to give the feel of calling out for despair or help. This piece of music has many elements which share much of modern jazz, for example, some of the compositions written by Keith Jarrett.